Behold the Alchemy of Black Gxrlhood

The expression “gumbo ya ya” is an expulsion of necessary noise. It is a cacophony of brilliance, of happenstance, of all of the beautiful, overwhelming sound that metamorphoses into its own vernacular. And just like the collection that bears its namesake, Aurielle Marie’s debut poetry book Gumbo Ya Ya! evokes a similar orchestral swell. Calling the melange of poems that reside in these pages a “book” or a “collection” doesn’t do Marie’s writing any kind of justice (especially because justice is a common theme in the work). Gumbo Ya Ya is at once gospel, praxis, translation, an archive, an offering, a mythology, a conjuring, a cartography of Blackness for us, by us. How glorious it is to traverse amongst these pages.

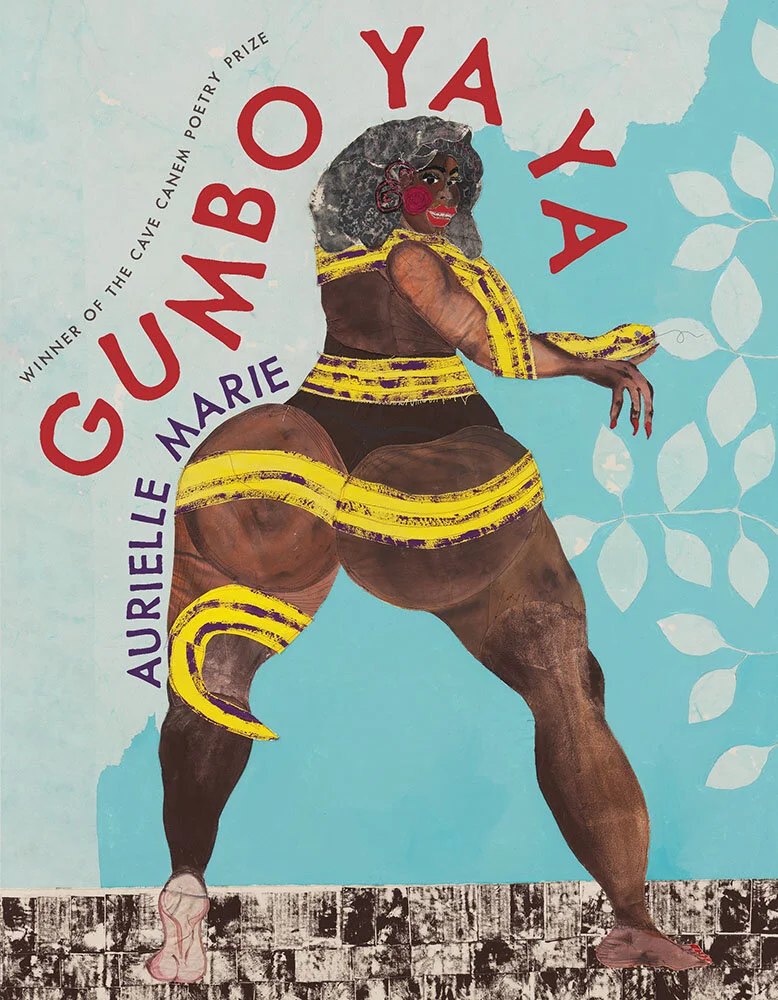

Gumbo Ya Ya by Aurielle Marie. University of Pittsburgh Press. 120 pages. $18.

The winner of the 2020 Cave Canem Poetry Prize, Aurielle Marie has come to claim her spot as one of the most dynamic poets to date. Gumbo Ya Ya is diligently observational. Marie sees things in landscapes that whiteness deliberately overlooks for the sake of self-preservation. She rebukes the necromancy of white supremacy, curses the charlatans that positions Black folk as subhuman, atrophied zombies, she clears away the dead growth for the reader to observe the bare meat beneath. “[F]olk gather at my palms to view / they own holes—” writes Marie, “wounds to mark where myths entered…” observing how Blackness is often the lens non-Black people articulate themselves through. The poems in this collection are a controlled burn; they clear away the dead leaves and debris, saturating the soil with nutrients, releasing seeds from cones and making space for new growth. Once the smoke dissipates, Marie does not seek to answer questions definitively, but instead offers possibilities. There is less emphasis on finding solutions, but more commitment to creating space for imagination so often stifled by white supremacy. Asé.

With no shortage of wit and a tender fierceness, Marie evokes the natural musicality and rhythm of Blackness. In her mojo bag, Marie holds an unbridled authenticity as she dazzles the reader with savory vernacular. Visually rich, she embraces the expansiveness of queer Black femme identity, rejecting siloed thought. The lens through which Aurielle Marie writes zooms in and out with ease. There are of course, the larger, structural harms that require larger systemic release, but these wounds make themselves known interpersonally, in the classroom, in the lines between the poem itself. By dissecting how white supremacy maintains itself through platitude and forgetfulness, Marie exposes these lies to the bone:

the ars poetica tempts its reader

into passive consumption. So, I divorce it. I mean to arrest

the hand of the man, hoist it with a scrap of frayed rope.

it is that simple, to write in praise of the metaphor

they used to kill us. even as the device itself lifts this page,

consider the violence -

Rarely is there writing that rejects the white gaze with such clarity and resolve. Marie challenges the poetry community to look deep within itself and recognize its own ability to enact harm. Poetry becoming synonymous with activism is more harmful than helpful. Through this meticulous deconstruction, the poet simply asks, at what cost do we hold our peace?

But navigating the intricate body and how it holds trauma, and how trauma is loaded onto Black humanity is yet another theme explored in this powerful collection. The nature of simultaneously being hyper-visible in the public eye and rendered invisible when lips are split open, carves itself into articulation through Marie’s conduit. Projections onto Blackness are almost hilarious in their dualisms; in white spaces the Black body (devoid of course, of personhood) is simultaneously degendered and hypersexualized. Regardless of how we are perceived, we are meant to be grateful for the scraps that we have built whole feasts from. In the eponymous poem “gumbo ya ya,” Marie pens this aforementioned dualism and its subsequent silencing:

heifer was my mother’s name, before she made me.

is no thief, though the product of it. My mother gave

birth to marauders. My mother came here to cash this speech in for fresh

vegetables. I was only allotted

my time. I was instructed to say thank you. Gratitude is tricky math.

I’d like to thank the academe for carving open my head. I’d like to

thank the academe for splitting my tongue.

I recognize that my work is all gristle, thank you, America

for stealing the meat. What’s the pronunciation of my name?

Marie writes for a population that is, in no small form, constantly at war, be it whether it be in the hood, in the country, in the MFA workshop, the art gallery, etc. The battles shape themselves distinctly with the times; in spite of upheaval, Marie celebrates Black queer joy, creates a language for articulating both joy and grief, creates a lyricism that allows for both to intertwine with each other. The language of the oppressor is set ablaze here. Marie embraces all of our different expressions of Black life, inventiveness, curiosity, desire. Gumbo Ya Ya is a reclamation of storytelling too, for as long as Black people have been rewritten through alternative gazes, we have illustrated our own narratives. Marie pays homage to those whose work gave further breath to Black life: Lorraine Hansberry, Warsan Shire, Noname, Zora Neale Hurston are just a few of the voices that are extended and venerated in this collection.

This collection too, is an elegy for Black gxrls whose lives were cut short at the hands of white supremacy. Marie rejects the zombification of the Black gxrl, instead choosing to celebrate the life lead, and the future possibilities of an unpained Black gxrlhood. Blackness is the lens through which the rest of the world articulates itself, and gentrification should be regarded as an erasure of Black culture and influence. Hence again, the battlefield, which is expressed in the poem “war strategies for every hood”:

from out our homes, flood the pleading faces of gentrifiers

bartering for mercy with china from our mothers’ closets

but we war blood now, cashed our mortgages in for machetes and kanekalon

our braid lynch cords slip into loops around their necks. held taut for small eternities

& then, finally let slack...

There is power in self-articulation, in the preservation of a culture that is so often considered the antithesis of humanity, as it does not serve the majority. And this self-articulation is made most clear in Marie’s poems about queerness. Marie writes about queerness as the opposite of scarcity, but the opportunity to transform relationship to desire and possible intimacies. Gender and Blackness bend into each other; there are moments of tenderness as Marie reflects on queer gxrlhood, moments of lament as the poet writes about gendered violence and the men who claim ownership over Black women’s sexuality. At the core of these vocalizations is a conjuring, a rootwork designed to free Black femme folks from the confines of both white supremacy and Black toxic masculinity. Marie invokes African deities with deference, gives praises to the inherent magic and alchemy that Black life lends itself to. As the poet grapples with helplessness, she bravely dives into the unknown, pulling out Black futures filled with grace, peace and comfort. At the center of these futures is revolution, is a necessary expulsion of all that plagues our communities, is both battle and community care. And comfort especially, is repossessed through Gumbo Ya Ya. Here, Black people are provided space to feel all of our feelings, to reflect on the past and turn a prophetic face towards the future.

Gumbo Ya Ya’s beautiful and striking imagery compliments an intrinsic gift of storytelling. When you step into the literature, you are not just reading words on a page, but entering a luminescent sensory experience. “I tell the truth about my own magics, and anger my mother’s iniquitous God” writes Marie in “unholy ghazal,” “I sharpen prayer into knives and kneel only for pleasure, now that I know better.” Be grateful, dear reader, and of course, take off your shoes and wash your soles before you set foot in the temple.